Ancient Indian education -By Miss Singh

Deathly blow to Indian universities

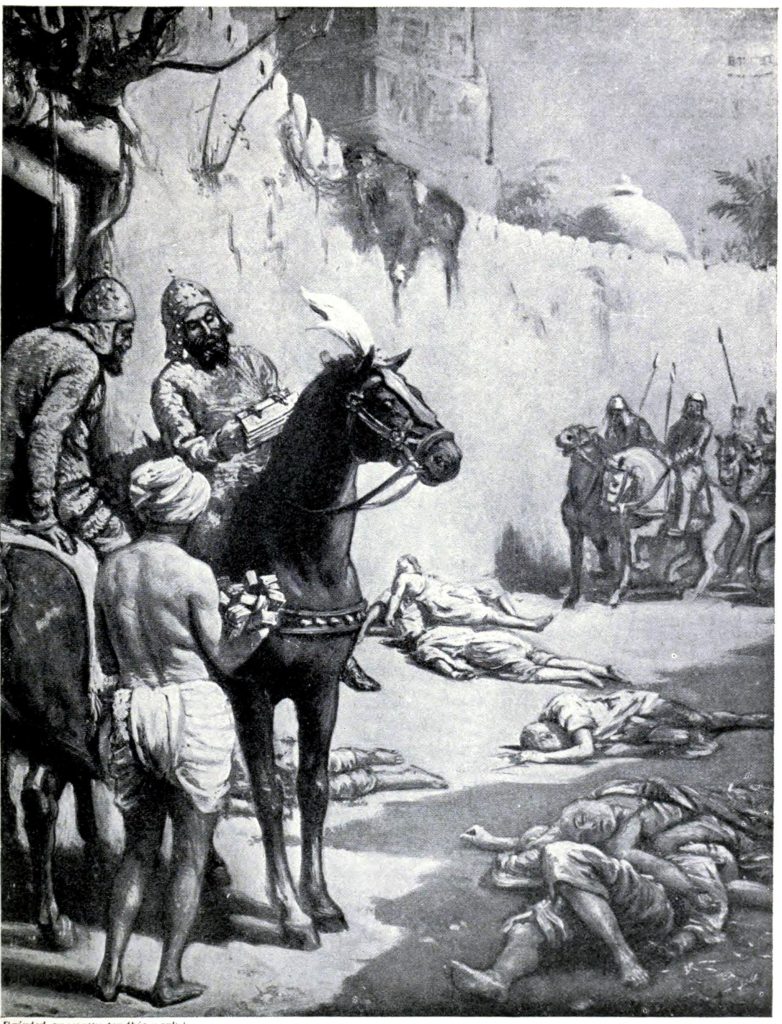

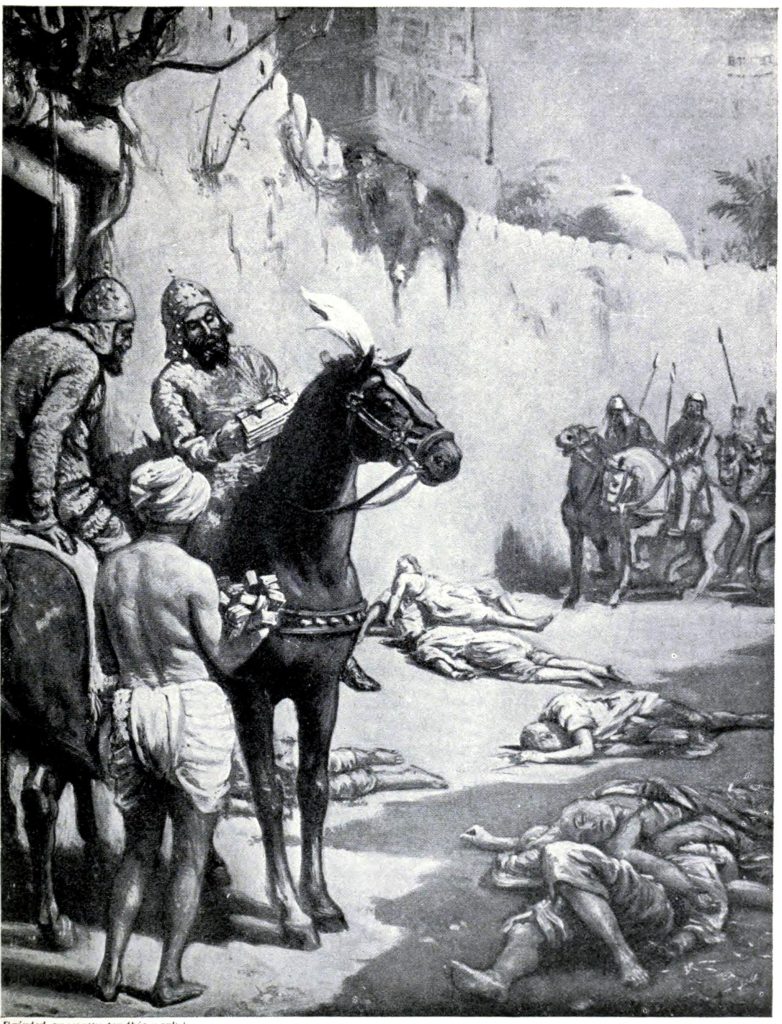

Imagine a group of horsemen riding into the campus of a world-famous university, mowing down students and professors until their bodies lie scattered everywhere. Imagine the same scene repeated at other universities, one after the other. And imagine all this in a time when there were no computers, no digital storage devices and no clouds to save the knowledge accumulated over generations. Mindless violence unleashed on the foremost universities of the time – Nalanda, Vikramshila and Odantapuri by Mohammad Bakhtyar Khilji and his men sent shock waves through Indic lands in the 13th century. The sacredness associated with institutions and persons of learning was violated in a manner never seen in India before.

The attack was chronicled by Minhaj-i-Siraj, principal historian of the Delhi Sultans in Tabaqat-i-Nasiri, who described the slaughter of thousands of “Brahmins” with shaven heads.

“There were a great number of books there; and, when all these books came under the observation of the Musalmans, they summoned a number of Hindus that they might give them information respecting the import of those books; but the whole of the Hindus had been killed.” (A.S.Altekar, 1944)

It is ironic that Bakhtyar Khilji hailed from a tribe in what is known as Afghanistan today, which practised Buddhism for centuries before being overrun by Ghaznavids and converting to Islam. In subsequent years, as Muslim rule spread and consolidated in different parts of India, many more universities were destroyed, such as Jagaddala, Somapura, Valabhi, Kashmir and others. As the news spread, scholars abandoned their colleges even before the Muslim invaders appeared. In Banaras, one of India’s ancient centres of education, when several hundreds of temples were destroyed by Qutubuddin Aibak in the 12th century, many learned Brahmins who taught there fled to southern India along with their families (A.S.Altekar, 1944). Some of the scholars who escaped from Vikramshila and other universities, such as Sakya Sribhadra and Vibhutichandra made their way to Tibet, another hub of higher learning (Mookerjee, 1960). Records maintained by Buddhist monks at Tibet give accounts of the destruction of Indian universities. Translations of Sanskrit texts preserved in Tibet help to give some idea of the books that were found in the libraries of the great Indian universities (Sharma R. N., 2012).

Had the rulers of India learned lessons from the earlier destruction of libraries in Alexandria, Cordoba, Persia and Ghazni (many of which contained texts that originated in India itself), and put their differences aside, perhaps India would boast of the world’s longest running universities today. More importantly, India would have retained its link with ancient works in Sanskrit, especially the ones on science and medicine. The destruction of key centres of higher education in India, including temples and the persecution of Hindus, Buddhists and other followers of Dharmic faiths during the centuries of Muslim domination affected the progress of Sanskrit scholarship considerably. The writing of new smritis and their revisions suffered a setback.

Historian A.L Srivastava has described the “325 years of Turko-Afghan rule” as a period of great suffering for Hindus, which were clearly not conducive to education, especially female education.

Not only were they deprived of their position as rulers, ministers, governors and commanders of troops, but were also treated contemptuously. The Turkish Sultans and their principal followers sought their brides from well-to-do Hindu families and compelled the proud chiefs to part with their daughters. In accordance with the Muslim law, the Hindu girls were first deprived of their religion, converted to Islam, and then married. (A.L.Srivastava, 1964)

The accounts of Brahmins fleeing to different parts of India to escape Muslim persecution are too many to be missed. Despite attempts by scholars to regroup in distant locations, and even to rebuild some of the destroyed universities, the old glory of Indic educational institutions could not be restored. The absence of science education that was noted by British chroniclers in a later era can be linked to the Muslim invasions of India. Sanskrit works of scientists and mathematicians of earlier periods began to be forgotten in their land of origin, even as their Arabic and Latin translations as well as plagiarised versions became the basis of science, mathematics and technology in Europe (See Part 2 of this article series).

Emphasis on Islamic Education

As the various Muslim dynasties got entrenched within India, education with the aim of imparting Islamic teachings became the norm. Muktabs and madrasas attached to mosques began to impart training in Islamic traditions. Says M.A. Khan in “Islamic Jihad: A Legacy of Forced Conversion, Imperialism and Slavery”:

Muslim rulers in India built only Islamic schools, namely muktabs and madrasas, often linked to mosques, solely for training Muslim students in their religion and other crafts for administrative and military duty, useful for the Muslim state. Learning Arabic and Persian language and memorizing the Quran, prophetic tradition and Islamic laws were the major subjects of study. Limited training was also given in agriculture, accountancy, astrology, astronomy, history, geography and mathematics, needed for running the state.

Muslim education was patronised by rulers from the Mamluk, Tughlaq and Lodhi dynasty as well as the Mughals and Bahmani Sultans. Delhi became one of the most important centres of Islamic learning (A.L.Srivastava, 1964). Other towns such as Jalandhar, Agra, Firozabad and provincial capitals also began to teach literature, philosophy and various humanities. The Islamic schools that used Persian as a medium of instruction were out of bounds for Hindu students. The lack of state support for education for Hindus led to a drastic decline in their higher education even though primary schools in villages continued to function wherever unjust taxation had not crippled finances completely. Many Hindus converted to Islam and learned Persian as a way of gaining respectable positions and to avoid the Jaziya tax imposed on non-Muslims. This was also a time when caste stratification became more rigid amongst Hindus in order to retain identities and preserve traditions.

Keeping Sanskrit and regional languages alive

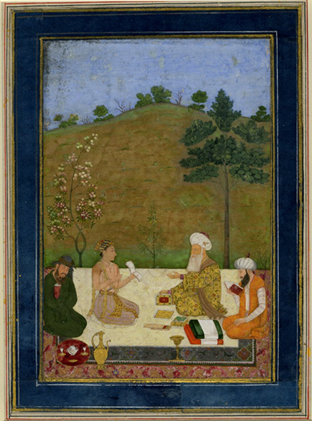

Rich businessmen, Hindu Rajas and local communities kept the flame of learning alight for Hindus (Dwivedi, 1994). During the reign of Mughal emperor Akbar (16th century), Sanskrit received some amount of royal patronage since the ruler was interested in harmonising relationships between his Muslim and Hindu subjects. The first Sanskrit-Persian dictionary was compiled during Akbar’s reign (Mehta, 1984). Many works were produced in Sanskrit, Hindi-Urdu and regional languages such as Bengali and Marathi. It was the age of Tulsidas and Rahim. Akbar was keen for students to not solely restrict themselves to theology and classical literature. In Ain-i-Akbari, which chronicles the reign of Akbar, it is stated:

Everybody ought to read books on morals, arithmetic, the notation peculiar to arithmetic, agriculture, mensuration, geometry, astronomy, physiognomy (the art of discerning character from the features of the face), household matters, the rules of government, medicine, logic, Tabiyi (natural science), Riyazi (higher mathematics) and Ilahi (metaphysics and theology), and history; all of which may be gradually acquired.

In studying Sanskrit, students ought to learn the Vyakarana, Nyaya, Vedanta and Patanjali. No one should be allowed to neglect these things which the present time requires” (Dwivedi, 1994).

Akbar also encouraged the opening up of Madrasas for Hindu children so that Hindus and Muslims could study side by side. He introduced the study of Sanskrit in many madrasas. His imperial library in Agra housed as many as 24,000 manuscripts. The books had attractive bindings and were beautifully illustrated. The king loved to listen to readings of books on a variety of subjects. Jain monks produced a number of Sanskrit works during Akbar’s reign. (Mehta, 1984)

To some extent, the encouragement of literature in Sanskrit and regional languages continued under the reign of Jahangir and Shah Jahan. Sanskrit poets such as Panditaraja Jagannatha and Kavindra Acharya Saraswati were patronized by Shah Jahan (Sarma, 1994). A new language emerged from the amalgamation of Persian, Arabic and Hindustani, which was similar to today’s Urdu and Hindi.

However, Aurangzeb reversed the inclusiveness that Akbar had ushered in during his reign. An Islamic fanatic, he persecuted Hindus and built new maktabs and madrasas on the ruins of demolished temples. (Riaz, 2008) On hearing that Brahmins at Thatta, Multan, Sindh and specially Varanasi were attracting Muslims to their discourses, he ordered all their temples and schools to be demolished (Mukhia, 2004). He killed his elder brother Dara Shikoh, the rightful heir to the throne, who was a Sanskrit scholar himself. With the help of pandits, Dara had translated Ramayana, Gita, Upanishads and Yogavasisthas to Persian; all of which constituted blasphemous acts in the eyes of his brother.

Dara’s Persian translation of Upanishads was translated to Latin in the beginning of the 19th century and created a renewed interest in the Upanishads among learned Europeans (Figueira, 1955). Had Dara become the emperor instead of Aurangzeb, India’s destiny could have been vastly different.

Neglect of sciences in the Mughal reign

The Mughals did not build on the leading-edge concepts presented by Hindu scholars of an earlier era to become the world leader in science and mathematics. While madrasas proliferated and students became adept in the finer details of the Quran and Hadiths in Muslim India, the western world was making advances in science and technology. Of course, these advances were considerably assisted by the Toledo school translations of Arabic works that were derived from India. (See Part 2 of this article). The Mughal kings missed the opportunity to ride the wave of technological discoveries in the west despite ruling over the richest land in the world. When Portuguese missionaries presented printed papers to Akbar, he was least interested in the potential of the printing press to transform education. His son Jahangir was similarly indifferent to a mechanical clock presented to him by the royal French delegation. (Riaz, 2008)

“The Mughal Empire has not produced a single worthwhile text on crafts or agriculture, how many volumes of poetry or histories it might have to its credit,” writes Irfan Habib (Habib, 2008). Apart from printing press and clocks, Mughal rulers were aware of nautical instruments, telescopes, pumps, various mechanical gadgets and wheelbarrows. Yet, these did not excite any desire for indigenous adaptation (Qaisar, 1982). The marvels of Mughal architecture were achieved without the aid of wheelbarrows (Kumar & Desai, 1982).

Arrival of the colonialists

Meanwhile, the Europeans who had been coming to India via the sea route from the 15th century onwards were battling amongst themselves for cornering the trade with India. The British East India Company emerged victorious after pushing the Portuguese, French and Dutch to the periphery and began spreading its tentacles within India. At first, the British did not bother themselves with education of the “natives” and focused on playing politics with different rulers and enriching themselves. Over time, they realised that “their dominion in India could not last long unless education – especially western – was diffused among the inhabitants of the land” (Basu, 1922).

A Mohammedan and a Sanskrit college were set up in Kolkata and Banaras respectively in the late 18thcentury “to provide a regular supply of qualified Hindu and Mohammedan law officers for the judicial administration” (Trevelyan, 1838). The British did not have any noble motives of education of the masses when they set up institutes of learning. These were the same people who imposed serious punishment on black slaves in America and passed laws to the effect that “assemblage of negroes for the purpose of instruction in reading or writing shall be an unlawful assembly” (Basu, 1922).

Anglicists versus Orientalists and their disdain for Indian knowledge

Many of us are familiar with Macaulay’s memorandum or “minute” on Indian Education, which was circulated by him prior to the passing of the English Education Act of 1835. That act gave effect to Governor-General William Bentinck’s decision of reallocating of funds towards a western curriculum with English as the language of instruction.

Thomas Babington Macaulay’s minute is a classic that needs to be read by every “educated” Indian:

“We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern – a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect. To that class we may leave it to refine the vernacular dialects of the country, to enrich those dialects with terms of science borrowed from the Western nomenclature, and to render them by degrees fit vehicles for conveying knowledge to the great mass of the population.”

Macaulay’s minute and the English Education Act came after a 15-year debate between the older faction of Orientalists and the later Anglicists. The Orientalists argued that government funds should be used to support colleges for the teaching of Arabic and Sanskrit, to pay stipends to the students at these colleges, and to translate works into Arabic and Sanskrit. The Anglicists on the other hand, advocated that these government funds should be spent on teaching English, with no stipends or translations at all. (Clive, 1971)

Most Orientalists and Anglicists had one thing in common – their belief in the “innate inferiority of the Indian culture” and the need to educate the elites (Clive, 1971). They only differed on how best to “improve” the minds of Indians, how to “correct” their beliefs and make them more useful as subjects of the British Empire.

Orientalists such as John Tytler believed in gradual reform via teaching in Arabic and Sanskrit so that the British could understand Indian culture and then prove it wrong. This method would lead to Indians themselves “correcting their countrymen”. (Clive, 1971)

Charles Trevelyan, brother-in-law of Macaulay and an avowed Anglicist, said before the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Government of Indian Territories that both “Hindoos and Mahomedans” regarded the British as “usurping foreigners” who had “taken the country from them” and excluded them from “the avenues to wealth and distinction”. He argued that European learning “would give an entirely new turn to the native mind”. The natives would cease to “strive after independence in the native model” and would not regard the British as “enemies and usurpers”, but as “friends and patrons, and powerful beneficent persons”. (Basu, 1922)

Trevelyan’s arguments against Sanskrit and Arabic as a means of instruction sound Kautilyan in strategy. Arabic literature would keep reminding Muslims that the British were “infidel usurpers” while Sanskrit texts would inform Hindus that their foreign rulers were “unclean beasts”. He pointed out that already in the army, there was a clear distinction between the English officers and the native sepoys. Not “one native out of 500” educated in Arabic in a seminary would be interested in enlisting in the army. Therefore, it was important to educate “sepoys” in English at the elementary level (Trevelyan, 1838). For the elites, English literature would do the trick. Familiarly acquainted with literature, the Indian youth would speak of great Englishmen with the “same enthusiasm” as the British themselves. They would reject the teachings of Brahmin priests. “The natives will not rise against us because we shall stoop to raise them,” he explained. Also, he noted that those educated in English would “cling” to the British rule because they would have everything to fear from a native government, which could mark them out for persecution. This last surmise of Trevelyan’s was clearly wrong, as the subsequent freedom movement of India proved.

Many Anglicists emphasised on the convenience attached to having English-speaking natives. Given that a large number of British officers were constantly being deputed in India, it was troublesome for them to understand the various languages and dialects of the natives. Also, it was a costly and time-consuming affair to translate various English books into native languages. In other words, the interests of the people of the land became subservient to convenience.

In addition to the Anglicists, there were the Vernacularists, who rejected Sanskrit and Persian in favour of regional languages. They championed the teaching of European knowledge in “vernacular” languages. The term “vernacular” itself has a derogatory meaning in the sense of being a language that is less cultured or refined.

Christian evangelism as a driver of education

It must be noted that spreading Christianity was a desirable goal for most Anglicists, Orientalists as well as Vernacularists. Dr Alexander Duff, an Anglicist, who opened a popular school in Calcutta was against “heathen” institutions. Macaulay himself wrote in a letter to his father, “No Hindoo who has received an English education ever remains sincerely attached to his religion.” He expressed his “firm belief” that if his plans of education were followed up, “there will not be a single idolator amongst the respectable classes in Bengal thirty years hence.” (Basu, 1922)

JC Marshman who made a sincere plea for retaining “Bengalee” as a medium of instruction gave the example of Serampore missionaries whose “labours” in “civilization and evangelization of the province of Bengal” had led to the establishing of 40 printing presses in a few decades and selling of 30,000 books in just one year. (Basu, 1922)

Many Christian missionaries learned regional languages such as Tamil and Kannada, published dictionaries in them and translated the Bible for evangelization activities. They appropriated several aspects of Hinduism into Christianity in order to make it more palatable to the locals and wean them away from traditional Sanatana Dharma.

English language struck roots in the land as the English Education Act began to take effect and the missionary schools that mushroomed across the country made English the “first language”.

Many Indians were Anglicists

An important argument made by Anglicists in favour of standardising English-medium education was that the Indian natives themselves were eager to learn English. “A taste for English has been widely disseminated,” said Trevelyan. He happily noted that a “loud call” arose from the natives themselves to be instructed in English. Schools teaching in English were extremely popular and English books were selling far more rapidly than books in Sanskrit and Arabic (Trevelyan, 1838). This is not surprising, since a good knowledge of English opened opportunities for government jobs all over the country. Besides, the vacuum in science and disconnect with Sanskrit works on science and mathematics caused by the Muslim rule made many Indians feel backward in comparison to the Europeans.

Raja Rammohan Roy is one of the most notable Indian Anglicists, who petitioned for the teaching of the “arts and sciences of modern Europe” and argued against establishing a new Sanskrit college in Calcutta in his letter to Lord Amherst. “The Sanskrit language, so difficult that almost a lifetime is necessary for its acquisition, is well known to have been for ages a lamentable check on the diffusion of knowledge; and the learning concealed under this almost impervious veil is far from sufficient to reward the labour of acquiring it,” he wrote. A new Sanskrit college, which taught the same things that were taught “two thousand years ago” would not help since ‘no improvement can be expected from inducing young men to consume a dozen of years of the most valuable period of their lives in acquiring the niceties of Byakaran or Sanskrit grammar,” he felt. Roy believed that giving allowances to the teachers engaged in teaching Sanskrit in different parts of India would be enough to keep the language alive and no new Sanskrit colleges were necessary. He was instrumental in the establishment of the Hindoo College in 1817 for imparting secular and scientific education, which later came to be known as the famous Presidency College of Kolkata. The alumni of the institute include outstanding personalities such as Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Satyendranath Bose and Meghnad Saha.

Dharampal’s revelations of astounding data on India’s popular schooling system

When India was embroiled in the education debate, England was itself languishing in illiteracy. A minuscule fraction of the children in England went to school, and the only book most literate people had read was the Bible. In the 1960s, Dharampal, a Gandhian thinker came across archival material of extreme significance in London. He discovered documents related to a series of surveys commissioned by the British government in the 19th century to assess the level of indigenous education in India. This set him on the path of pioneering research, which brought up startling data. He discovered Thomas Munro’s statement that almost every village in India had a pathshala (school). There were 100,000 village schools reported in Bengal and Bihar alone in the 1830s. Reading, writing, arithmetic, epics and more were being taught. William Adams, one of the surveyors has written that he could not recollect studying in his village school in Scotland anything that had more “direct bearing” upon daily life than what was taught in the “humbler village schools of Bengal”. (Dharampal, 2000)

From different parts of India came reports of dedicated teachers, superior methods of teaching and high school attendance. But what simply challenged every stereotype was that in a large number of schools, “Soodras” were in majority while the Brahmins and “Vysees” were in minority. In Tamil-speaking areas, the Shudras ranged from 70% in Salem and Tinnevelly to over 84% in South Arcot. In Malayalam-speaking Malabar, Brahmin students constituted only 20% of schools, while Shudras were 54% and Muslims were 27%. The same trend was reported in Kannada-speaking Bellary and Oriya-speaking Ganjam. Only in the Telegu-speaking districts, the dwija castes formed the majority of students. Some collectors who furnished data spoke about poor Brahmins who taught children with no expectation of compensation. Girls were mostly home-schooled. However, in the Malabar district as well as “Jeypoor Zamindari of Vizagapatam district”, the percentage of girls was close to 30%, a very high number. (Dharampal, 2000)

It must be remembered that schooling was not the only way of transmitting basic education. Artisans, craftsmen and agriculturalists taught their skills to apprentices via a separate system of education.

A.D.Campbell, the collector for Bellary applauded the “economical” teaching methods in Indian schools and the system of “more advanced scholars” teaching the “less advanced” thereby confirming their own knowledge. He mentioned that this method “well deserved the imitation it had received in England”. He was referring to the “Madras Method” of teaching, which was introduced by Reverend Andrew Bell in England. Dr Bell had been impressed by little children in Madras writing with their fingers on sand, which “after the fashion of such schools had been strewn before them for that purpose”. He saw a system of children learning from peers. After Dr Bell published his paper on Madras Method, he was in great demand to introduce this in British schools. By 1821, 300,000 children were reportedly being educated under Dr Bell’s principles and his ideas were adopted in Europe, West Indies and even Bogota, Colombia. (Tooley, 2009)

The Beautiful Ecosystem is uprooted

As the British rule progressed in India, villages got increasingly impoverished. For example, when the British with the Nawab of Arcot attacked Thanjavur in 1771 and imposed taxes as high as 59% of gross produce, they created mass poverty overnight! The entire British administrative apparatus was geared towards fleecing the citizens and even the designations of officers such as “District Collectors” indicated that the only aim of the government was to collect taxes. One collector of Bellary was so moved by the plight of the people that he wrote a letter to the authorities that the degeneration of education was attributable to the “transfer of capital of the country from the native government…to the Europeans, restricting it by law from employing it even temporarily in India and daily draining it from the land.” Further, he wrote, “The means of the manufacturing classes have been greatly diminished by the introduction of our own European manufactures.”(Dharampal, 2000)

The British educational policies also sounded the death knell for regional languages as the rush for English-medium education intensified. With every subject being taught in English and mother-tongues being relegated to “second language” the quality of literature in regional languages began sinking. Illiteracy and low self-confidence began to be associated with absence of English proficiency. M.K.Gandhi said in 1931 that the British had left India more illiterate than it was a hundred years ago. Today, India has the largest number of illiterate in the world.

Disturbingly, India’s self-gaze is still through alien eyes. The past heritage lies buried in regional and Sanskrit literature, awaiting illumination. When India became independent from the British in 1947, there was a fresh opportunity to write a new chapter of decolonization.

India is still waiting.

The author would like to acknowledge the critical inputs of the members of Indian History Awareness and Research (IHAR). She would also like to express gratitude to Rare Book Society of India and Nikhil Dureja for generously sharing books that provided key references for writing this article.

Works Cited

A.L.Srivastava. (1964). The Sultanate of Delhi 711 to 1526 AD. Shiva Lal Agarwala.

A.S.Altekar. (1944). Education in Ancient India. Nand Kishore and Bros.

Apte, D. Universities in Ancient India.

Basu, B. D. (1922). History of Education in India Under the Rule of the East India Company. The Modern Review Office.

Bose, M. (1990). A Social and Cultural History of Ancient India. Concept Publishing Company.

Clive, J. (1971). The debate on Indian education: Anglicists, Orientalists and the ideology of Empire.

Dharampal. (2000). The Beautiful Tree. Other India Press.

Dwivedi, B. L. (1994). Evolution of Educational Thought in India. Nothern Book Centre.

Figueira, D. M. (1955). Translating the Orient- The Reception of Sakuntala in Nineteenth Century Europe. State University of New York Press.

Habib, I. (2008). Technology in Medieval India. Tulika Books.

Kumar, D., & Desai, M. (1982). The Cambridge Economic History of India Vol 2. Cambridge University Press.

Mehta, J. (1984). Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India. Sterling Publishers Pvt Ltd.

Mookerjee, R. K. (1960). Ancient Indian Education – Brahminical and Buddhist. Motilal Banarsidass.

Mukhia, H. (2004). The Mughals of India. Blackwell Publishing.

Qaisar, A. (1982). Indian Responses to European Technology and Culture. Oxford Universoty Press.

Riaz, A. (2008). Faithful Education: Madrassahs in South Asia. Rutgers University Press.

Sarma, N. (1994). Panditaraja Jagannatha – The Renowned Sanskrit Poet of Medieval India. Mittal Publications.

Sharma, R. N. (2000). History of Education in India. Atlantic Publishers.

Sharma, R. N. (2012). Libraries in the early 21st century, volume 2: An international perspective. De Gruyter Saur.

Tooley, J. (2009). The Beautiful Tree – A personal journey into how the world’s poorest people are educating themselves. Cato Institute.

Trevelyan, C. E. (1838). On the Education of the People of India.

Feature Image Credit: Erik Törner

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. IndiaFacts does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Sahana Singh writes on Indian history. She is a member of Indian History Awareness and Research (IHAR), and has recently authored “The Educational Heritage of Ancient India – How An Ecosystem of Learning Was Laid to Waste”.

2. An stone lithographed copy of Adhyatam Ramayan printed in Lahore 1903.

2. An stone lithographed copy of Adhyatam Ramayan printed in Lahore 1903.